I recently had the opportunity to interview Jeremy Yon, Industry Relations Leader, GE Current, a Daintree company, and Chair of the NEMA Luminaire Section UGR Task Force, on the topic of application of the Unified Glare Rating (UGR) metric. This interview was conducted to inform an article that will be published in the September 2022 issue of ELECTRICAL CONTRACTOR, the official publication of NECA. Transcript follows.

DiLouie: NEMA recently published LS 20001-2021, a whitepaper concerning current use of UGR as a glare metric. What was the rationale behind producing this whitepaper?

Yon: Glare is a timeless and universal concern to everyone who cares about lighting. It is one of the most critical aspects of an occupant’s experience with lighting and one of the most devilishly difficult topics. Historically, glare comes in and out of fashion. Because LED efficacy is now slowly increasing, glare is returning to the forefront of the industry’s attention. This topic has been grappled with by true lighting visionaries in the past, and now my NEMA colleagues and I are attempting to re-structure how glare is thought of and talked about so that there can be a common understanding and vocabulary when working together with all stakeholders.

DiLouie: What does UGR, overall and in general, reliably deliver, and what are its limitations?

Yon: The broad aim of UGR is to provide a better way to evaluate glare in indoor settings. However, it is not a simple matter because UGR depends strongly on the specific application; not only in regards to the luminaires, but also in their layout, the shape of the room and the reflectances of the surfaces in the room all affect the value of UGR. Additionally, the location of people in the room and the tasks conducted within the room can affect the experience of glare as well, so different values of UGR may be desired in different applications.

Therefore, we believe much of the confusion and misunderstanding when it comes to UGR is due in part to the three different ways that the term is used – they each have their own purposes and limitations. Since they were unnamed previously, we’ve taken the liberty to recommend that they be called Application UGR (UGRAppl), Luminiare UGR (UGRLum), and Point UGR (UGRPoint).

We’ve come to understand through our research that Application UGR and Point UGR can be tools for lighting designers to get predict what will likely be the visual comfort level for specific locations within an application. These are not absolute determinations and must be balanced with other predictive factors. Application UGR was designed while, and works best when, considering a windowless rectangular room with regularly spaced luminaires (think troffers). Point UGR is possible with computer simulations, but it should not be evaluated by looking at each point as it requires averaging over an area by the user to achieve the intended indication of comfort.

Luminaire UGR is the most common use of the term today and is the most problematic use of the equations. The UGR methodology was not intended to be an absolute measurement. The Luminaire UGR approach does this by forcing an evaluation of a single luminaire type in a specific evaluation space without taking into consideration the space itself (geometry, room finishes, luminaire placement, windows, partitions, multiple luminaire types, etc.). It cannot appropriately predict the likelihood of glare in any space other than that single specifically required condition. NEMA advises strongly against using Luminaire UGR.

DiLouie: What are the most common misconceptions practitioners have about glare and UGR, and what is the reality they should understand?

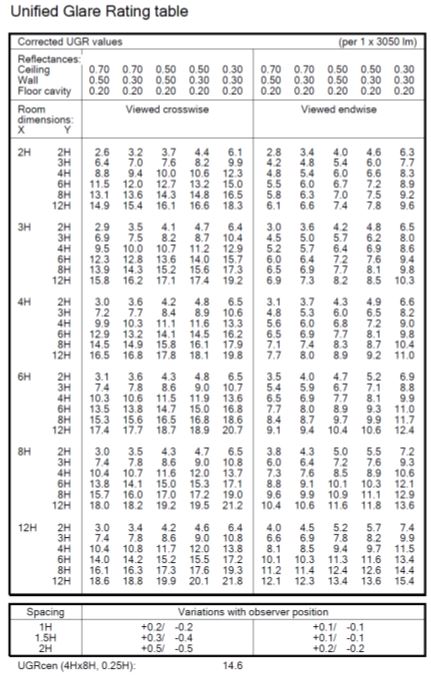

Yon: I think the most common misconception is to assume that a luminaire can have a UGR rating, ignoring the role of the application. If you look at a table of values produced by the tabular method for a single luminaire, you will see that, depending on the light distribution of the luminaire, the UGR can vary greatly. It clearly does not depend only on the luminaire. Below is an example in which UGR varies from 2.6 to 21.8.

While some may claim that UGR is the best of the various limited glare evaluation tools, that doesn’t mean UGR can deliver more than it is capable. Unless properly evaluated for the specific application in which a luminaire will be used, it can’t give absolute assurance that the luminaire selected is going to meet the required lighting design criteria. To this point, some manufacturers refuse to put Luminaire UGR numbers on their cutsheets. They don’t want to contribute to a misuse of the UGR metric, nor have their customer be the victim of poor lighting design quality because of a misapplied UGR number.

DiLouie: DLC, LEED, and WELL specify a maximum UGR based on glare emitted by the luminaire (UGR-Lum). This offers an advantage of reducing glare to a simple number published on a catalog sheet. NEMA says there are significant disadvantages. What are they?

Yon: All of those rating programs use the Luminaire UGR simplification to get the single value you mention. This creates a situation where a designer thinks they are selecting a product that has the “right number,” but in actuality, they may be selecting one that has more glare than is desired in application. From the example given earlier, the tabular reporting of that luminaire had a range of values from 2.6 to 21.8 – just based on room size and no other factors. With a variation this wide, it simply makes no sense to try and represent a luminaire with a single number.

Because of the selection of only a single reported value, there are many factors that impact the visual experience found in the final application that are not incorporated into Luminaire UGR. Some examples include the room finish (a dark ceiling will be much different than a light ceiling), the luminaire mounting height (high-bay vs office), and non-uniform placement (troffer grids vs artistic slots).

At the same time, luminaires that are designed to achieve only a Luminaire UGR value, and not to minimize glare from an application approach, can have various consequences. The luminous surfaces of the luminaires may be less uniform with easier-to-see LEDs, there may be additional accessories that need to be installed and there may be a feeling that the final spaces are darker, even though there may be adequate horizontal light (some may remember the deep-parabolic troffer days of the 1980s).

DiLouie: NEMA believes UGR-Appl, adopted by ISO and EN 12464-1, is a more appropriate metric to use to predict glare in a space…

Yon: NEMA is saying that UGR should be used in the way intended by the original CIE documents. Simplifying it to a luminaire based value is not correct.

DiLouie: Some organizations utilize UGR-Point, which predicts glare at a point in the space. This similarly places the metric in the space, not at the luminaire, but NEMA cautions about its use. Why?

Yon: Simulations will produce an array of point UGR values in a space. The original UGR uses a “trick” to calculate the average UGR over a 1H x 1H square centered along the walls. If only point calculations are done, as simulation software typically does, then the averaging step is omitted. Judicious positioning of the luminaires and/or the point for calculation can result in large variations in the UGR. “Cherry picking” from a set of UGR point values can yield a misleading value for UGR.

In examples given in the NEMA paper, UGR tables include a variation expectation that is often overlooked. These show expected point-to-point variation values, depending on the spacing of the luminaires. In the example we provided, the variation ranges from a minimum of +3/-3 units to +7.5/3.8 units, making a comparisson against a threshold impossible.

The user of a piece of software should perform proper averaging, either as detailed in the UGR standard (in a 1H x 1H region at the center of two adjacent walls) or in certain situations where occupants are only in specific areas, such as custom areas that best represent their design objectives. Secondly, there are some ambiguities in the UGR standard around handling different sizes of luminaires that can lead to differences between software simulations.

Finally, and most importantly, the designer needs to balance the results with all the other aspects of a lighting design – vertical illumination, presence/design of windows, space use flexibility, circadian exposure objectives, etc.

DiLouie: If UGR-Appl is most advantageous in predicting glare, a challenge is that the procedure appears to be complex and not well understood. What is the solution for this?

Yon: It is complex and not well understood! The fundamental CIE UGR standard (117) has been around since 1995. But oversimplifying it will lead to artificial selection of some luminaires as “good” and others as “bad,” when in fact the goodness/badness is impossible to evaluate outside of the context of the application. With the absence of a simple answer, it is good for all of us to remember that lighting, by definition, is a blending of art and science. This balance is what makes it so interesting and engaging for most of us.

The first recommendation is that luminaires should be used in the manner in which they were intended; if a high bay luminaire is used in an office, there is probably going to be a difference in visual comfort than if a luminaire designed specifically for an office is used. Building on this notion, manufacturers play an important role in determining what appropriate use is. The literature should be clear, and specifiers should ask for details they feel will help complete the project. A qualified lighting professional should be used to bring together all the complexities of lighting into an optimized solution.

Finally, and most importantly, all stakeholders need to come together with researchers to provide consistent and actionable recommendations. The IES is tackling this for some product categories and there is hope for continued engagement. Internationally, there is still work to be done by the CIE.

DiLouie: How should electrical contractors evaluating lighting systems approach it in regards to ensuring a product will not produce objectionable glare? Are there rules of thumb for evaluating application glare?

Yon: The most important rule of thumb is that glare, at its essence, is related to the difference between a bright object and a dark background. This is easy to see in daily life – high-beam headlights that can be disabling at night are barely visible during the day. The first step is to factor in the surfaces around the luminaire – are they light or dark finished? Is there light from other sources hitting the surface to keep it from being dark? The luminaire should fit into those needs by providing diffuse light in circumstances where an overall lighter environment is warranted, controlled and shielded when a dark atmosphere is expected.

It always helpful to think of the extremes – a soft white uniformly backlit luminous ceiling and white walls (if not overly bright) can have almost no glare (to the point that it can be disorienting); whereas a black-box theater goes to extremes to hide the source of the light so as to not draw attention away from the performance. Similarly, luminaires for offices would most likely be expected to have a uniform appearance and contribute to lighting the walls and surfaces, while task-specific lights (such as a wall-wash or a high-bay warehouse aisle light) rely on precision optics that need to be coordinated with the overall viewing expectations of occupants.

DiLouie: What other solutions does NEMA recommend as a way to ensure lighting systems are designed and delivered that minimize glare while serving the best needs of the application?

Yon: The first is to recognize how UGR can be both properly and improperly utilized as a guidance method for good lighting design. We’re hopeful that through the NEMA whitepaper, it is understood that only Application UGR provides suitable guidance in terms of what an occupant will experience in a specific space. In addition, if simulations are done, the individual point UGR values should not be utilized (averaging should be done) and there are assumptions about large and small luminaires that may lead to variations of answers in different software platforms.

Certainly, there is more study and work to be done to improve how we predict glare. It is hopeful that further focus and effort can be made that will simplify how this is done. Yet for now, Application-UGR remains our best option. What we don’t want is a misunderstood lighting metric, such as Luminaire-UGR, being used in good faith efforts to simplify the situation, as this will result in poor outcomes in lighting performance.

DiLouie: If you could tell the entire electrical industry only one thing about UGR, what would it be?

Yon: Our message to the industry is that UGR is an imperfect predicter of glare, but Application UGR is the best method we have today. With the right understanding, it can be an asset to lighting design application. If UGR’s limitations are not understood, such as using Luminaire UGR as a singular number inaccurately across a variety of applications, it undermines the purpose of the metric and can result in poor lighting.

DiLouie: Is there anything else that you’d like to add about this topic?

Yon: NEMA members place a high value on the visual environments our luminaires create. We work together with designers, installers and users to balance the needs of an application to create the most appropriate experience. Balanced factors like efficacy, color rendering, color temperature, uniformity, light distribution, color consistency, etc. all can have different impacts on the perceived glare for each specific application that cannot be factored into a single-value luminaire value.

NEMA welcomes the opportunity to work with all the stakeholders in evolving means to both predict and communicate expectations for visual comfort. Today, Application UGR and averaged Point UGR calculations can be an effective part of an overall lighting design, but they are very limited and should not be applied as a luminaire selection tool.

You must be logged in to post a comment.